|

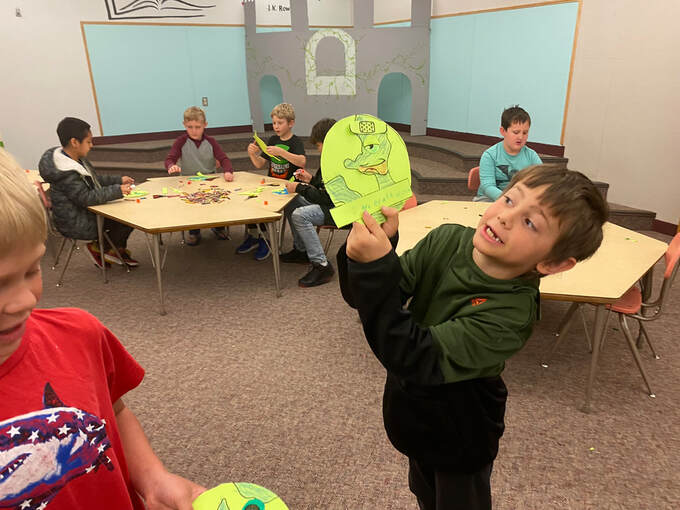

Keep Chadron Beautiful recently served as a community partner to Chadron Primary School when the school held the first session of their summer enrichment program for local students. There were approximately 30 students in attendance daily, ranging from Kindergarten to 2nd grade. KCB’s mission as they designed their lessons was to afford students with education on litter awareness, while focusing on how different environments were impacted by pollution. The primary environments discussed were land, air, and water. During the two weeks of the program, KCB’s Educational Director, Stephanie Glass, lead a long term experiment that allowed students to create observations on plants that had various aspects of their environment modified or withheld. Six plants were provided for students to observe, one receiving all elements of care (water, soil, sunlight, and oxygen), the others each had one element of care withheld. To demonstrate the impact of toxins on the plants, an additional plant was watered with vinegar. “It was wonderful to watch the kids get excited about the changes these plants went through each day,” stated Ms. Glass, “they were so quick to make connections and respond to the way the plants changed with their environments. Putting students in the role of being scientists allowed them to feel ownership over the results of our activity, and it’s definitely an educational element I think KCB will use in the future.” Perhaps the most popular lesson during the program involved a toy turtle, who came in and told a story to the children about his experience with ocean waste, and was interviewed by the children on how litter and waste in the ocean had impacted him. During subsequent lessons, the children often asked how the turtle was doing, and if his part of the ocean had been cleaned up, demonstrating their investment in his narrative.

When asked how KCB’s involvement with the Just For Kids program and with the more recent summer program had benefited the Chadron Primary School, After School Program Director, Lorna Eliason stated the partnership had resulted: “in more Chadron youth being served with free high quality, sustainable expanded learning opportunities throughout the school year and summer.” The Primary School Summer program resumes for its final week from August 1st-4th, 2022. Keep Chadron Beautiful will be there, excited to assist with the ecological education of our community's students.

1 Comment

I often think about the habits that I want to incorporate as permanent changes in the routine of my life. From getting a workout in everyday, to brushing my teeth every evening, to tracking my spending after each purchase. But how do we get from a place of wanting to build a habit, to actually building one? Some are easy. For example, it is very easy for me to read to my son before bedtime. This is both because it is highly enjoyable, and because he actively reminds me about book time and is heartbroken if we miss it. But then there are other habits, deep cleaning the fridge every month, or spending time working on music theory during guitar practice… not just playing the few songs I know over and over again on a loop. Some habits are harder to build than others. I might go through the day with positive intentions, but when I get to the point of execution—that’s when I wobble. But, before we go too far down this rabbit hole, here’s a bigger question: what the heck does habit building have to do with a blog on litter reduction and recycling? Simple answer: everything. Let me expand on that.

According to an article from the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, How we Form Habits, Change Existing Ones: “Studies show that about 40 percent of people’s daily activities are performed each day in almost the same situations.” Often, we form habits without much thought. For instance, turning on the TV when we get home after work. If a parent possessed this habit, this might have been ingrained in us during childhood. This is often a habit people state they don't want to have, because it takes up a great deal of time. If we choose our habits, and decide to build positive ones into our lives, then we can take the automated, habit driven 40 percent of our daily lives and make it far more useful and far more goal driven. If we have goals related to litter reduction and recycling, then those goals are something we can build our habits upon. In choosing our habits, we are choosing how we are spending our time. Here's a few examples of waste reducing habits we can build:

All of these actions help the environment. All of these actions involve building new habits. Something that I’ve learned in my own recent quest to understand how habit building works, is that we humans tend to have a limited amount of willpower. For me, at least, I think of my willpower like my phone battery. I recharge overnight and wake with a full battery (most of the time), throughout the day. So, I tend to make my best choices in the morning. But each choice I make drains a bit of my battery. If I can find ways to make my habits as easy as possible (reducing the number of choices I have to make to accomplish my goals) then they are infinitely more likely to actually happen, instead of ending up on the backburner because I’m too tired to put in the work. For example, if my goal is to take my son on a litter walk in the evenings, I’m far more likely to accomplish this goal if I make it a habit to leave trash bags and plastic gloves by the front door. If my goal is to use reusable bags at the grocery store, the easiest way to make sure I actually do so is to make sure that the bags “live” in my car. Not my kitchen. Even if it is easier after unloading my groceries to just shove them under the kitchen sink. Basically, I’ve found that to implement and cement new habits into the ritual of my life, the best thing I can do is anticipate my own laziness while taking into account my goals and setting myself up for success. In Gretchin Rubin’s book on habit building, “Better than Before”, she says, “A habit requires no decision from me, because I’ve already decided.” If we can take our positive goals and make our decisions about how we want to accomplish them, and then ingrain those decisions into our lives, that is when we’ve created a habit. Like setting a Roomba to clean our living rooms while we’re away, we can set up our habits to help us accomplish our daily, yearly, and lifelong goals. Have you ever thought of making your own compost to fertilize and nourish your vegetable garden and flower beds? Backyard composting is one way to keep the city of Chadron a beautiful and healthy place to live. Composting is an easy and environmentally friendly way to recycle food scraps from your kitchen and dried leaves and grass clippings from your yard and turn them into nutrient rich fertilizer for the soil. To make a composting container only requires minimal supplies and the results are a natural healthy fertilizer that recycles waste that would otherwise end up in the landfill, and it helps to save money you would have spent on fertilizers and soil-enhancers to feed your plants.

Making compost does not require rocket science. It is a simple and cost-effective process. However, you must keep in mind that too much of one type of matter can affect the smell and texture of your compost. In order to keep your yard smelling pleasant, you have to tend what goes into your compost pile. Teulon (2014) says, “The ideal compost pile is a balance of brown and green matter. Too many leaves, which are high in carbon, can slow it down. Too many grass clippings, which are high in nitrogen, and the pile may starve itself of oxygen and go anaerobic (another word for smelly).” The “brown” or carbon matter in your compost could include straw, shredded cardboard, and dried leaves. Vegetable peelings and fresh grass clippings are considered “green” matter and will help to balance the pile because they are high in nitrogen. The cheapest method for composting is to dig a small hole somewhere in your yard and dump your compost there. This method does not require any tending, but it will take a lot longer for the matter to break down into usable compost, sometimes up to two years. If you want to speed up the composting process, you have to turn and mix your compost pile every once in a while, so that fresh air and insects can help to break it down faster. Because fresh air is one of the key factors to speeding up the composting process, many people choose to make compost bins using wood slats and chicken wire. They leave spaces between the wood so that all the compost in the bin is getting access to air. This helps the compost pile to break down evenly. Another method that is popular among hobby farmers and gardeners is the compost tumbler. Compost tumblers are obviously more expensive than just digging a hole in the ground or using a few pieces of wood, but they save a lot of time and effort that would be spent turning your compost pile and the composting process can be accelerated. Teulon (2014) states: "If your pile or drum holds more than 1 cubic metre of waste, the decomposition can become so rapid that temperatures soar, helping heat-loving, or thermophilic bacteria to flourish. If your compost is turned and aerated on a regular basis, the thermophilic bacteria will remain active and can raise temperatures upwards of 150°F (66°C), quickly breaking down plant material, killing off seeds and plant pathogens. Comparatively, a small composter or pile will not reach such high temperatures, which could lead to a composting time of roughly two years for the same amount of waste." A natural cooking process occurs which helps heat-loving bacteria to breakdown the material and change it into a useful fertilizer for your garden. Composting is a great way to keep Chadron beautiful because it recycles the kitchen scraps and yard waste that would otherwise go into the dumpster to rot and smell up our neighborhoods. The composted material fertilizes plants and makes them healthier and more productive. Flowers bloom for longer periods and vegetable gardens will be more productive. Composting is simple and cost effective, and is something that people of all ages can do to help the environment and beautify our community. Reference: Teulon, W. (2014). Backyard Composting. Gardens West, 28(6). Recycling has been important to me since long before I came to Chadron State College, so naturally, when I moved into the dorms on campus my recycling habits followed me from home. In December of 2019, I had taken a tour of campus and was delighted to see blue recycling receptacles along the sidewalks. In passing they seemed very useful; three openings in each bin made a place for trash, glass, and cans. Upon arriving at CSC for the fall term, however, I discovered that all three openings in each bin emptied into a singular bag, which included trash, so no recycling was being done. I thought to myself, "What the heck? Isn't this a state college? Why aren't we recycling here? Who green-lighted this?" and continued to look for areas to put my plastics. There was no recycling bin by the dumpsters, in the cafeteria, the dorms, or any building for that matter.

The lack of proper receptacles did not keep me from recycling, though. Over the weeks I would put my rinsed recyclables in trash bags and take them to my hometown Aurora whenever I drove back to visit my family. Glass items that I could not recycle in either town I would keep rather than throwing them away, including pickle jars and kombucha bottles, which now live happily on my dorm room windowsill among my house plants. During the semester there would be weeks in between me collecting recyclables and taking them home to properly dispose of because I was only able to make the 6-hour trip a handful of times. As each day passed and bag after bag would fill, I realized that I, as a singular person, produce a lot of trash! This isn't to say I am wasteful, but over time I would bring three or four bulging bags of cardboard, plastic bottles, and milk jugs home. Looking at the number of recyclables I produce alone, I began to think about how many students there are on campus producing the same amount or more of recyclables every day. Personally, I utilize the cafeteria for the majority of my meals and only really need groceries for the weekend. I also utilize reusable bottles instead of buying plastic ones. Despite not buying a lot of products every week, I still somehow manage to produce loads of recyclables at the end of the month. As I sit here and type, three bags of plastics sit in my spare bedroom closet waiting for the semester to end so that I can eject them from my dorm and into my recycling bin at home. Keeping this in mind, I thought about the people who do the exact opposite. My suitemate, for example, buys a 24-pack of water bottles weekly, and I know for a fact he does not believe recycling is important. In his words, "Who cares?" so, he throws all 24 bottles in the garbage by the end of the week, and buys another 24 every weekend to repeat the cycle. Well, I care. Because there are hundreds of students on campus, and with no place to put their bottles and boxes, the dumpster is where all of it ends up. Out of the hundreds of students living on campus, how many do you think are going out of their way to drive their plastics to another city? Not a lot, because college kids don't have the time or energy to do that, let alone afford the gas. This is why the school needs to provide places for students to recycle. I love that we have water dispensing stations because they promote reusable bottles, but that is not enough to make up for the milk jugs, cardboard, tin cans, glass, and non-bottle plastics being thrown in the garbage on campus. I am definitely not an expert, but I had a few ideas regarding how to combat this problem. For the dorms, there are too many students using too many items to have just one receptacle in the lobby or outside. I think that having one bin per floor would allow easy access for each number of students, and promote recycling by being just a few feet away. Students leave their dorm to put their trash in the chute, so have recycling bins accessible too! But who would empty the bins when they are full? Well, the Resident Advisor of each floor could. Once per week, wheel the bins down via the elevator or stairs to larger receptacles outside. Recycling is not heavy like trash, most of it is air-filled bottles, empty cans, and cardboard, so bringing the bins down a flight of stairs would not be a hazardous task. Then the next problem would be getting all of it out of the city. There is a recycling drop-off in Rapid City according to Google Maps, and I think bi-monthly trips would allow us to remove the recycling collected at a productive rate. The rest needs more research to be done, and sadly this is just a humble blog, so I will not be doing that here today. I think the campus needs some sort of environmentalist club that could raise awareness, funds, and sponsor the implementation of a recycling program on campus. Perhaps a mini 'Keep Chadron Beautiful' student-led group? I don't know. What I do know is that we are throwing away an inappropriate amount of recyclable items on campus, and in the rest of the town as well. The population of Chadron is over 5,000, and if each person is producing even one trash bag worth of recyclables per month (and we all know that one bag per person per month is an unrealistically small hypothetical), that's well over 5,000 bags of items that are going in the garbage instead of being repurposed. We need to do better.

As you'll see in this video, it took me a while to share the footage from my waste audit. I was working to tackle feelings of guilt over the trash that I was producing and the harm that I felt I was causing on an environmental level. Basically, I was overcomplicating my relationship with waste and waste reduction to the point where it made it very hard for me to examine it, accept how I was producing trash, and work toward a way of managing my waste. Thankfully though, since I had conducted my waste audit and written in my journal about my goals, and then edited the video of the waste audit, I had no choice but to meditate on my choices and think about how I wanted to move forward on my waste reduction journey.

After filming, I put the video away for as long as I could. A few months passed and I knew: I had to complete the project I had started. I sat at my desk, staring at the footage I was attempting to edit, wanting nothing more than to trash the video and start from scratch, projecting myself as the environmental ideal rather than expressing my flaws for an audience. But I changed my mind. I decided to take a walk in a place that reminded me why environment should be a priority, I decided to draw attention to how I had been feeling instead of pushing those feelings down. I doubt that I am alone in feeling guilt, shame, and confusion over the waste I've produced. If these feeling are something you connect with, you aren't alone. In my role as education coordinator for Keep Chadron Beautiful, I find the only way I can operate is to focus on just doing a little bit better within a daily, weekly, monthly, or yearly frame. I might learn a little bit more or implement a few better practices in my life, and to do so in a way that allows them to become habit. If we try to achieve great, substantial changes in the course of a four day weekend they don't tend to be the changes that stick. However, numerous small scale choices, over broad expanses of time--those stick. Those make a difference. And when others--our children, our friends, or our coworkers--see those changes, we often can become leaders and bring about much greater change. But, and this is important: we must be gentle with ourselves as we grow. In Litterology: Understanding Littering and the Secrets to Clean Public Spaces, Karen Spehr and Rob Curnow offer insight into the psychology of litter and study how people are influenced to litter—or not—based on the design of public places. As the Education Coordinator for Keep Chadron Beautiful, a large part of my position is to inform my community regarding the ecological risks surrounding litter and working toward community wide litter prevention. So, this book was right up my alley.

The authors, two environmental psychologists located in Australia, weight the book with a significant amount of data on the topic of litter, which makes for a very informative read. They also incorporate statistical information from their own well-developed study on how people make decisions such as using a bin, and/or littering. However, they share the information they have compiled in a way that is easily comprehendible for someone without a background in the science and psychology of litter. Perhaps one of the greatest strengths of this book is how the authors place an emphasis on destabilizing pre-existing bias regarding who litters (they argue that people from every demographic litters relatively equally), and instead place the focus on what causes people to litter in specific places. By doing this, Litterology encourages the use of litter observation in public spaces prior to attempting to solve littering behaviors. For instance, while someone working toward reducing litter at a public park might be inclined to immediately add more bins to the location, through observation they might find that a band of rogue racoons is scattering litter across the space during the night. Once the racoons have had their fun, the lessened cleanliness of the park might increase littering behaviors in those who frequent the space. While the initial impulse, putting out additional bins, is a well-intentioned attempt at a solution, it wouldn’t solve the actual problem. I was afraid that a book on litter might try to shame the reader out of the act of littering, rather than educating and informing in a way that helps change behavior. This fear was, thankfully, unfounded. Spehr and Curnow take great care to focus their book not on shaming people, but rather on how to develop spaces in a way that naturally, through the psychology of community and shared public spaces. They argue: “It hardly seems surprising that more bins, fines, or promotional campaigns fail to hit the park as one-off solutions to what is essentially a more complicated and long-term problem. Also, if you think about littering behaviors rather than litterers, it leads you to ask questions about what led to this behavior and what can be done about it” (Spehr and Curnow). What can be done about it? Litterology offers insight into that as well. Perhaps the most significant insight into the psychology of littering behavior that I gained from this book, is that people are naturally inclined to keep beautiful spaces beautiful. If a place is clean, it generates a sense of community and there is a greater likelihood that community members will maintain that cleanliness through bin usage, or even picking up trash and litter that they did not themselves produce. In addition, Litterology names the various types of littering, from “wedging”, “undertaking”, to “clean sweeping”. By breaking down littering behavior into specific types, we can see, even more closely, how to work towards designing spaces that help break these littering cycles. Litterology is not aimed at only the academic, it is intended for anyone with an interest in preventing litter and beautifying community spaces. Accordingly, the research is laid out in a way that can be understood by anyone, academic in the field and general reader alike. More specifically, while the authors’ main intent is to inform the reader as to psychological aspects of littering, this book is written in a way that it will appeal to those invested in city planning or general beautification of both outdoor and indoor spaces. The text does reiterate the main argument a bit too often for my taste. However, this recursive style of argumentation helps get the message across effectively. Litterology is an excellent addition to the library of anyone who is interested in understanding the psychology behind littering behaviors, and how we can all work to influence the creation and maitenence of beautiful public spaces. The winter holidays are a wonderful source of family, cheer, and light in our lives at the end of the year. There’s nothing I love more than curling up with some hot chocolate and a book next to a fire, twinkle lights glowing on the Christmas tree. But what can we do to enjoy our holidays while staying mindful of the waste we’re creating? What’s the best way to dispose of old Christmas lights, is there a better way to wrap Christmas presents? How can we celebrate the holidays without contributing to the excess waste that already threatens our earth?

Here are a few suggestions for how we can do a little better this year:

It only takes a few steps to make a big impact. This Christmas, let’s give back to the Earth by investing a little bit of extra time and care in the way we handle our waste. Food waste is perhaps one of the easiest and most important areas of waste reduction that we can focus on in our daily lives. According to the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), "up to 40 percent of the food in the United States in never eaten." We must consider the significance of this statement both through the lens of current food insecurity statistics, and through the ecological damage producing this excess waste creates when the food goes to the landfill and produces a damaging greenhouse gas called methane (NRDC). According to Yale Climate Connections, "As much as 11 percent of greenhouse gas emissions could be eliminated if food waste were brought to zero" (Spiegel). Clearly, food waste has a dramatic impact on climate change and the condition of our earth. On a smaller level, another consideration is that by minimizing food waste in your own home you have the opportunity to dramatically lower your grocery bill. From a broad view, one of the most important changes we can make as a country is to focus on "implementing strategies that prevent surpluses of food from occurring in the first place" (Spiegel). One of these primary sources of detrimental emissions is from animals raised for food. KCB isn't suggesting that you adhere to a vegan lifestyle unless that is something which you feel is right for you, however, considering incorporating "Meatless Monday" (or Thursday, lol) into your weekly diet could lower the demand placed upon the meat industry and subsequently help to lower the demand for animal products. While some level of responsibility falls upon the consumer to implement personal strategies to make sure that they aren't creating food waste, we can also consider the impact of the seller and how they package the meat and other animal products which are on the market. Incorporating simple additions, such as highly legible dating on product packaging, makes a difference. Sellers also need to be held accountable for over-production of food products. Participating in programs which send excess food to low-income families is one way that companies can work to avoid detrimental food waste. But how can we as individuals reduce the amount of food waste we produce?

The process of reducing food waste in the home is one that comes down to mindfulness. Be aware. Invest your time and care into how you structure the way purchase, store, prepare, and consume your food items. Each small change has the potential to create positive change for the better. Resources: FDA. Tips to Reduce Food Waste. https://www.fda.gov/food/consumers/tips-reduce-food-waste NRDC. Food Waste, What's at Stake. https://www.nrdc.org/food-waste Spiegel, Jan Ellen. (2019). Food Waste Starts Long Before Food Gets To Your Plate. Yale Climate Connections.https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2019/05/food-waste-has-crucial-climate-impacts/?gcli

|

AuthorStef Glass is the Education Coordinator for Keep Chadron Beautiful. She graduated from Chadron State College with her BA in English Literature and minors in History and Creative Writing in May of 2018. Archives

June 2022

Categories |

||||||||

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed